What Art Form Did They Transition to After Cave Paintings

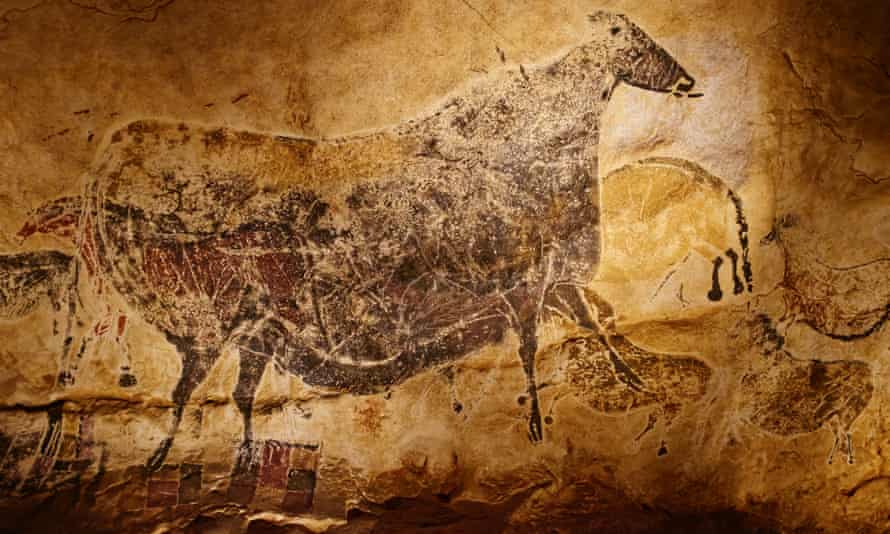

I n 1940, 4 teenage boys stumbled, almost literally, from German-occupied France into the Paleolithic age. As the story goes – and at that place are many versions of it – they had been taking a walk in the forest near the town of Montignac when the dog accompanying them suddenly disappeared. A quick search revealed that their animal companion had fallen into a pigsty in the ground, and so – in the spirit of Tintin, with whom they were probably familiar – the boys made the perilous 15-metre descent to discover it. They institute the canis familiaris and much more, especially on return visits illuminated with alkane lamps. The pigsty led to a cave, the walls and ceilings of which were covered with brightly coloured paintings of animals unknown to the 20th-century Dordogne – bison, aurochs and lions. Ane of the boys afterward reported that, stunned and elated, they began to dart around the cavern like "a band of savages doing a war trip the light fantastic". Another recalled that the painted animals in the flickering light of the boys' lamps seemed to be moving. "We were completely crazy," notwithstanding another said, although the build-up of carbon dioxide in a poorly ventilated cave may have had something to exercise with that.

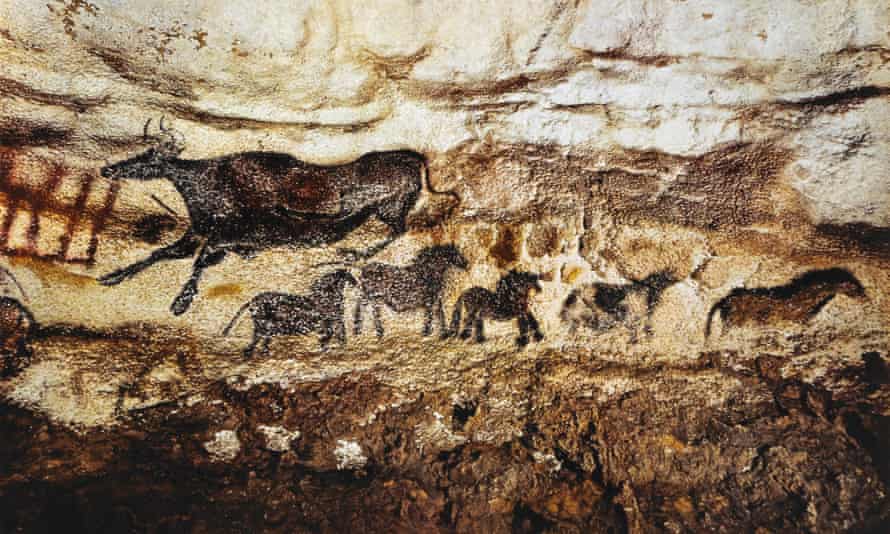

This was the famous and touristically magnetic Lascaux cavern, which eventually had to be closed to visitors lest their exhalations spoil the artwork. Today, almost a century later, we know that Lascaux is part of a global phenomenon, originally referred to as "busy caves". They have been found on every continent except Antarctica – at least 350 of them in Europe alone, thank you to the cavern-rich Pyrenees – with the virtually recent discoveries in Borneo (2018) and Republic of croatia (April 2019). Uncannily, given the distances that carve up them, all are adorned with like decorations: handprints or stencils of homo hands, abstract designs containing dots and crosshatched lines, and large animals, both carnivores and herbivores, nearly of them at present extinct. Not all of these images appear in each of the decorated caves – some feature simply handprints or megafauna. Scholars of paleoarcheology infer that the paintings were made by our distant ancestors, although the caves contain no depictions of humans doing whatsoever kind of painting.

At that place are human-like creatures, though, or what some archeologists cautiously phone call "humanoids", referring to the bipedal stick figures that can sometimes exist found on the margins of the panels containing animal shapes. The non-human animals are painted with nigh supernatural attention to facial and muscular particular, but, no doubt to the thwarting of tourists, the humanoids painted on cave walls have no faces.

This struck me with unexpected force, no doubtfulness considering of my own particular historical situation, almost twenty,000 years afterward the creation of the cave art in question. In most 2002 nosotros had entered the age of "selfies," in which everyone seemed fascinated by their electronic cocky-portraits – clothed or unclothed, made-upward or natural, partying or pensive – and determined to propagate them every bit widely every bit possible. Then, in 2016, the The states caused a president of whom the kindest affair that can be said is that he is a narcissist. This is a sloppily defined psychological condition, I admit, just fitting for a human so infatuated with his own image that he decorated the walls of his golf clubs with imitation Fourth dimension magazine covers featuring himself. On top of all this, nosotros have been served an eviction notice from our own planet: the polar regions are turning into meltwater. The residents of the southern hemisphere are pouring n toward climates more hospitable to crops. In July, the temperature in Paris reached a record-breaking 42.6C.

Yous could say that my sudden obsession with cave fine art was a pallid version of the boys' descent from Nazi-dominated France into the Lascaux cave. Articles in the New York Times urged distressed readers to take refuge in "cocky-care" measures such every bit meditation, nature walks and massages, just none of that appealed to me. Instead, I took intermittent breaks from what we presumed to phone call "the Resistance" by throwing myself downwardly the rabbit hole of paleoarcheological scholarship. In my case, information technology was non only a matter of escape. I found myself exhilarated by our comparatively ego-free ancestors, who went to not bad lengths, and depths, to create some of the world's most breathtaking art – and didn't even bother to sign their names.

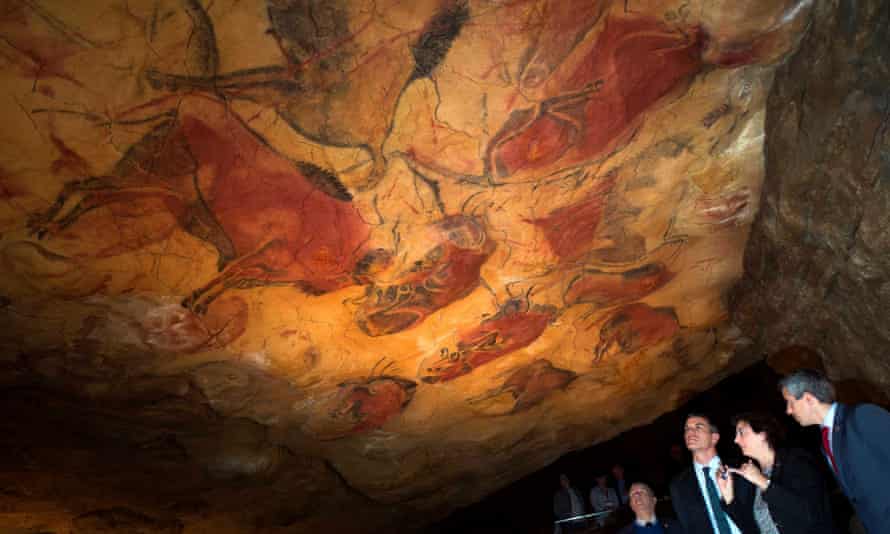

C ave art had a profound outcome on its 20th-century viewers, including the young discoverers of Lascaux, at least one of whom camped at the hole leading to the cave over the winter of 1940-41 to protect information technology from vandals, and perhaps Germans. More illustrious visitors had similar reactions. In 1928, the creative person and critic Amédée Ozenfant wrote of the art in the Les Eyzies caves, "Ah, those hands! Those silhouettes of easily, spread out and stencilled on an ochre ground! Become and see them. I hope you the nearly intense emotion you lot have always experienced." He credited the Paleolithic artists with inspiring modern art, and to a certain degree, they did. Jackson Pollock honoured them by leaving handprints along the summit border of at least ii of his paintings. Pablo Picasso reportedly visited the famous Altamira cave before fleeing Spain in 1934, and emerged saying: "Beyond Altamira, all is decadence."

Of form, cavern art also inspired the question raised by all truly arresting fine art: "What does it mean?" Who was its intended audience, and what were they supposed to derive from it? The boy discoverers of Lascaux took their questions to one of their schoolmasters, who roped in Henri Breuil, a priest familiar enough with all things prehistoric to be known as "the pope of prehistory". Unsurprisingly, he offered a "magico-religious" interpretation, with the prefix "magico" serving as a slur to distinguish Paleolithic behavior, whatsoever they may accept been, from the reigning monotheism of the modern world. More practically, he proposed that the painted animals were meant to magically attract the bodily animals they represented, the improve for humans to hunt and eat them.

Unfortunately for this theory, it turns out that the animals on cavern walls were not the kinds that the artists usually dined on. The creators of the Lascaux art, for example, ate reindeer, non the much more formidable herbivores pictured in the cave, which would have been difficult for humans armed with flint-tipped spears to bring down without being trampled. Today, many scholars reply the question of pregnant with what amounts to a shrug: "Nosotros may never know."

If sheer marvel, of the kind that drove the Lascaux discoverers, isn't enough to motivate a search for improve answers, there is a moral parable reaching out to the states from the cavern at Lascaux. Shortly after its discovery, the one Jewish boy in the grouping was apprehended and sent, forth with his parents, to a detention middle that served as a stop on the style to Buchenwald. Miraculously, he was rescued by the French Red Cross, emerging from captivity as peradventure the only person on globe who had witnessed both the hellscape of 20-century fascism and the artistic remnants of the Paleolithic age. Equally we know from the archeological record, the latter was a time of relative peace among humans. No doubt there were homicides and tensions between and within human bands, just information technology would exist at to the lowest degree some other 10,000 years before the invention of war equally an organised collective activeness. The cave art suggests that humans once had better ways to spend their time.

If they were humans; and the worldwide gallery of known cave fine art offers and then few stick figures or bipeds of any kind that we cannot exist entirely sure. If the Paleolithic cave painters could create such perfectly naturalistic animals, why non requite united states of america a glimpse of the painters themselves? Virtually as foreign as the absence of human images in caves is the low level of scientific interest in their absence. In his book What Is Paleolithic Art?, the world-class paleoarcheologist Jean Clottes devotes but a couple of pages to the outcome, last that: "The essential role played past animals manifestly explains the small number of representations of human beings. In the Paleolithic world, humans were not at the heart of the stage." A paper published, oddly enough, past the Usa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, expresses puzzlement over the omission of naturalistic depictions of humans, attributing it to Paleolithic people's "inexplicable fascination with wildlife" (not that there were whatever non-wild animals around at the time).

The marginality of man figures in cave paintings suggests that, at least from a homo betoken of view, the cardinal drama of the Paleolithic went on betwixt the various megafauna – carnivores and large herbivores. And then depleted of megafauna is our own earth that it is hard to imagine how thick on the ground large mammals once were. Even the herbivores could be dangerous for humans, if mythology offers any clues: think of the buffalo demon killed by the Hindu goddess Durga, or of the Cretan half-human being, one-half-bull Minotaur, who could only be subdued past confining him to a labyrinth, which was, incidentally, a kind of cave. Just as potentially edible herbivores such as aurochs (behemothic, at present-extinct cattle) could be dangerous, death-dealing carnivores could be inadvertently helpful to humans and their human-like kin, for case, by leaving their half-devoured prey backside for humans to finish off. The Paleolithic landscape offered a lot of big animals to watch, and enough of reasons to keep a close center on them. Some could be eaten – subsequently, for example, beingness corralled into a trap by a band of humans; many others would readily consume humans.

Yet despite the tricky and life-threatening relationship between Paleolithic humans and the megafauna that comprised and then much of their environment, 20th-century scholars tended to claim cave art equally evidence of an unalloyed triumph for our species. It was a "great spiritual symbol", 1 famed fine art historian, himself an escapee from Nazism, proclaimed, of a time when "man had just emerged from a purely zoological existence, when instead of beingness dominated by animals, he began to dominate them". But the stick figures institute in caves such as Lascaux and Chauvet do not radiate triumph. By the standards of our own time, they are excessively self-effacing and, compared to the animals portrayed effectually them, pathetically weak. If these faceless creatures were actually grinning in triumph, we would, of course, have no manner of knowing it.

W eastward are left with i tenuous clue as to the cave artists' sense of their status in the Paleolithic universe. While archeologists tended to solemnise prehistoric art every bit "magico-religious" or "shamanic," today'due south more secular viewers sometimes detect a vein of sheer silliness. For instance, shifting to another time and painting surface, Republic of india'south Mesolithic rock art portrays few human being stick figures; those that are portrayed have been described past modern viewers as "comical," "animalised" and "grotesque". Or consider the famed "birdman" epitome at Lascaux, in which a stick figure with a long, skinny erection falls backwards at the approach of a bison. As Joseph Campbell described information technology, operating from inside the magico-religious paradigm: "A large bison bull, eviscerated by a spear that has transfixed its anus and emerged through its sexual organ, stands before a prostrate man. The latter (the only crudely drawn effigy, and the simply human figure in the cave) is rapt in a shamanistic trance. He wears a bird mask; his phallus, erect, is pointing at the pierced bull; a throwing stick lies on the footing at his feet; and beside him stands a wand or staff, bearing on its tip the image of a bird. And then, behind this prostrate shaman, is a large rhinoceros, apparently defecating as it walks away."

Take out the words "shaman" and "shamanistic" and you have a description of a crude – very crude – interaction of a humanoid with 2 much larger and more powerful animals. Is he, the humanoid, in a trance or just momentarily overcome by the forcefulness and beauty of the other animals? And what qualifies him as a shaman anyway? The bird motif, which paleoanthropologists, drawing on studies of extant Siberian cultures, automatically associated with shamanism? Similarly, a bipedal figure with a stag's head, institute in the Trois Frères cave in French republic, is awarded shamanic status, making him or her a kind of priest, although, objectively speaking, they might as well exist wearing a political party hat. As Judith Thurman wrote in the essay that inspired Werner Herzog's picture The Cave of Forgotten Dreams, "Paleolithic artists, despite their penchant for naturalism, rarely chose to depict human beings, and then did and so with a crudeness that smacks of mockery."

Merely who are they mocking, other than themselves and, by extension, their distant descendants, ourselves? Of course, our reactions to Paleolithic fine art may bear no connection to the intentions or feelings of the artists. Yet at that place are reasons to believe that Paleolithic people had a sense of humour not all that dissimilar from our own. After all, we practice seem to share an aesthetic sensibility with them, as evidenced past modernistic reactions to the gorgeous Paleolithic depictions of animals. As for possible jokes, nosotros take a geologist's 2018 report of a series of fossilised footprints found in New Mexico. They are the prints of a behemothic sloth, with much smaller human footprints inside them, suggesting that the humans were deliberately matching the sloth's footstep and following it from a close altitude. Exercise for hunting? Or, equally one scientific discipline writer for The Atlantic suggested, is there "something almost playful" almost the superimposed footprints, suggesting "a bunch of teenage kids harassing the sloths for kicks"?

Then there is the mystery of the exploding Venuses, where nosotros once again encounter the sparse line between the religious and the ridiculous. In the 1920s, in what is now the Czech Commonwealth, archeologists discovered the site of a Paleolithic ceramics workshop that seemed to specialise in carefully crafted footling figures of animals and, intriguingly, of fat women with huge breasts and buttocks (although, consistent with the mode of the times, no faces). These were the "Venuses," originally judged to exist either "fertility symbols" or examples of Paleolithic pornography.

To the consternation of generations of researchers, the figures consisted almost entirely of fragments. Shoddy adroitness, perhaps? An overheated kiln? Then, in 1989, an ingenious team of archeologists figured out that the clay used to make the figurines had been deliberately treated and then that it would explode when tossed into a fire, creating what an art historian called a loud – and ane would retrieve, unsafe – display of "Paleolithic pyrotechnics." This, the Washington Mail service'due south account ended ominously, is "the earliest evidence that human created imagery only to destroy it".

Or we could expect at the behaviour of extant stone age people, which is by no means a reliable guide to that of our distant ancestors, but may incorporate clues as to their comical abilities. Evolutionary psychiatrists signal out that anthropologists contacting previously isolated peoples such every bit 19th-century Indigenous Australians found them joking in ways comprehensible even to anthropologists. Furthermore, anthropologists written report that many of the remaining hunter-gatherers are "fiercely egalitarian", deploying sense of humor to subdue the ego of anyone who gets out of line: "Yep, when a young homo kills much meat he comes to think of himself as a master or a large man, and he thinks of the balance of usa as his servants or inferiors," i Kalahari hunter told the anthropologist Richard B Lee in 1968. "Nosotros can't accept this. Nosotros refuse one who boasts, for someday his pride volition make him kill somebody. So we ever speak of his meat every bit worthless. This way we cool his heart and make him gentle."

Some lucky hunters don't expect to exist ridiculed, choosing instead to disparage the meat they take acquired equally soon as they arrive back at military camp. In the context of a shut-knit human group, cocky-mockery tin exist cocky-protective.

In the Paleolithic age, humans were probably less concerned nigh the opinions of other humans than with the actions and intentions of the far more numerous megafauna around them. Would the herd of bison stop at a certain watering hole? Would lions show up to assault them? Would it be safe for humans to grab at whatever scraps of bison were left over from the lions' meal? The vein of silliness that seems to run through Paleolithic art may grow out of an accurate perception of humans' place in the world. Our ancestors occupied a lowly spot in the food chain, at least compared to the megafauna, only at the same time they were capable of understanding and depicting how lowly it was. They knew they were meat, and they likewise seemed to know that they knew they were meat – meat that could retrieve. And that, if yous think about it long enough, is almost funny.

P aleolithic people were definitely capable of depicting more realistic humans than stick figures – human figures with faces, muscles and curves formed past pregnancy or fat. Tiles found on the floor of the La Marche cave in France are etched with distinctive faces, some topped with caps, and have been dated to fourteen-fifteen,000 years ago. A solemn, oddly triangular, female face carved in ivory was found in late 19th-century France and recently dated to about 24,000 years ago. Then in that location are the higher up mentioned "Venus" figurines constitute scattered about Eurasia from about the same fourth dimension. But all these are pocket-size and were apparently meant to be carried around, like amulets, perhaps – as cave paintings obviously could non be. Cave paintings stay in their caves.

What is it virtually caves? The attraction of caves as fine art studios and galleries does not stem from the fact that they were convenient for the artists. In fact, there is no evidence of continuous human habitation in the busy caves, and certainly none in the deepest, hardest-to-access crannies reserved for the near spectacular animal paintings. Cave artists are non to be confused with "cavemen".

Nor exercise nosotros need to posit any special human analogousness for caves, since the fine art they contain came down to us through a unproblematic process of natural pick: outdoor fine art, such as figurines and painted rocks, is exposed to the elements and unlikely to last for tens of thousands of years. Paleolithic people seem to have painted all kinds of surfaces, including leather derived from animals, also equally their own bodies and faces, with the same kinds of ochre they used on cave walls. The difference is that the paintings on cave walls were well enough protected from pelting and wind and climatic change to survive for tens of millennia. If there was something special most caves, it was that they are ideal storage lockers. "Caves," every bit paleoarcheologist Apr Nowell puts it, "are funny little microcosms that protect paint."

If the painters of Lascaux were aware of the preservative properties of caves, did they anticipate future visits to the same site, either past themselves or others? Earlier the intrusion of culture into their territories, hunter-gatherers were "non-sedentary" people – perpetual wanderers. They moved to follow seasonal animal migrations and the ripening of fruits, probably fifty-fifty to escape from the human faeces that inevitably piled upward around their campsites. These smaller migrations, reinforced by intense and oscillating climate change in the Horn of Africa, added up to the prolonged exodus from that continent to the Arabian peninsula and hence to the residue of the globe. With so much churning and relocating going on, it's possible that Paleolithic people could excogitate of returning to a decorated cave or, in an even greater spring of the imagination, foresee visits by others like themselves. If then, the cave fine art should exist thought of as a sort of hard drive, and the paintings as information – and not only "Hither are some of the animals you will encounter effectually hither," only also "Here nosotros are, creatures like yourselves, and this is what we know."

Multiple visits by different groups of humans, possibly over long periods of time, could explain the foreign fact that, every bit the intrepid French boys observed, the animals painted on cave walls seem to be moving. There is zero supernatural at work here. Expect closely, and y'all see that the animal figures are usually composed of superimposed lines, suggesting that new arrivals in the cave painted over the lines that were already there, more than or less like children learning to write the messages of the alphabet. And then the cave was non merely a museum. It was an art school where people learned to paint from those who had come before them, and went on to apply their skills to the next suitable cave they came beyond. In the process, and with some help from flickering lights, they created animation. The movement of bands of people across the landscape led to the credible movement of animals on the cave walls. As humans painted over older artwork, moved on, and painted again, over tens of thousands of years, cave art – or, in the absence of caves, rock art – became a global meme.

There is something else about caves. Non just were they storage spaces for precious artwork, they were too gathering places for humans, perhaps up to 100 at a time in some of the larger chambers. To paleoanthropologists, especially those leaning toward magico-religious explanations, such spaces inevitably propose rituals, making the busy cavern a kind of cathedral within which humans communed with a higher power. Visual art may take been only one part of the uplifting spectacle; recently, much attention has been paid to the acoustic backdrop of busy caves and how they may have generated awe-inspiring reverberant sounds. People sang, chanted or drummed, stared at the lifelike animals effectually them, and perhaps got loftier: the cave as an ideal venue for a rave. Or maybe they took, say, psychedelic mushrooms they institute growing wild, and so painted the animals, a possibility suggested past a few modern reports from San people in southern Africa, who dance themselves into a trance state earlier getting down to work.

Each ornament of a new cave, or redecoration of an old one, required the commonage effort of tens or peradventure scores of people. Twentieth-century archeologists liked to imagine they were seeing the work of especially talented individuals – artists or shamans. Merely every bit Gregory Curtis points out in his volume The Cavern Painters, it took a crowd to decorate a cavern – people to inspect the cavern walls for cracks and protuberances suggestive of megafauna shapes, people to haul logs into the cavern to construct the scaffolding from which the artists worked, people to mix the ochre paint, and still others to provide the workers with food and h2o. Careful analysis of the handprints institute in so many caves reveals that the participants included women and men, adults and children. If cave art had a function other than preserving information and enhancing ecstatic rituals, it was to teach the value of cooperation, which – to the signal of self-sacrifice – was essential for both communal hunting and commonage defence.

In his book Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari emphasises the importance of collective endeavour in the evolution of mod humans. Private skill and courage helped, but and so did the willingness to stand with one'southward band: not to scatter when a dangerous brute approached, not to climb a tree and leave the baby behind. Mayhap, in the ever-challenging context of an animal-dominated planet, the need for homo solidarity so far exceeded the need for individual recognition that, at to the lowest degree in artistic representation, humans didn't need faces.

A ll this cavern painting, migrating and repainting came to an finish roughly 12,000 years agone, with what has been applauded as the "Neolithic revolution". Lacking pack animals and perhaps tired of walking, humans began to settle downwardly in villages, and eventually walled cities; they invented agriculture and domesticated many of the wild animals whose ancestors had figured so prominently in cave art. They learned to weave, brew beer, smelt ore and craft ever-sharper blades.

But whatever comforts sedentism brought came at a terrible price: holding, in the form of stored grain and edible herds, segmented societies into classes – a procedure anthropologists prudently term "social stratification"– and seduced humans into warfare. War led to the institution of slavery, especially for the women of the defeated side (defeated males were commonly slaughtered) and stamped the entire female gender with the stigma attached to concubines and domestic servants. Men did ameliorate, or at to the lowest degree a few of them, with the most outstanding commanders ascent to the status of kings and eventually emperors. Wherever sedentism and agriculture took hold, from China to Southward and Fundamental America, coercion by the powerful replaced cooperation among equals. In Jared Diamond's edgeless cess, the Neolithic revolution was "the worst fault in the history of the human race".

At least it gave us faces. Starting with the implacable "female parent goddesses" of the Neolithic Heart East, and moving on to the sudden proliferation of kings and heroes in the Bronze Age, the emergence of human faces seems to marker a characterological change – from the solidaristic ethos of small, migrating bands to what we now know as narcissism. Kings and occasionally their consorts were the first to enjoy the new marks of personal superiority – crowns, jewellery, masses of slaves, and the arrogance that went along with such things. Over the centuries, narcissism spread downward to the bourgeoisie, who, in 17th-century Europe, were beginning to write memoirs and commission their own portraits. In our own time, anyone who can afford a smartphone can propagate their own epitome, publish their most fleeting thoughts on social media and burnish their unique brand. Narcissism has been democratised and is available, at least in crumb-sized morsels, to usa all.

So what exercise nosotros demand decorated caves for any more? One disturbing possible employ for them has arisen in just the final decade or so – as shelters to hide out in until the apocalypse blows over. With the seas rising, the weather turning into a serial of psychostorms, and the earth's poor becoming ever more restive, the super-rich are buying upward abased nuclear silos and converting them into doomsday bunkers that tin can house upward to a dozen families, plus guards and servants, at a time. These are fake caves of course, merely they are wondrously outfitted – with pond pools, gyms, shooting ranges, "outdoor" cafes – and busy with precious artworks and huge LED screens displaying what remains of the outside world.

But it's the Paleolithic caves we need to return to, and not just because they are still capable of inspiring transcendent experiences and connecting us with the long-lost natural globe. We should be drawn back to them for the message they have reliably preserved for more 10,000 generations. Granted, it was non intended for u.s.a., this bulletin, nor could its authors have imagined such perverse and cocky-destructive descendants as we have become. But it's in our hands at present, still illegible unless we push back hard confronting the artificial dividing line between history and prehistory, hieroglyphs and petroglyphs, between the "primitive" and the "advanced." This volition take all of our skills and knowledge – from art history to uranium-thorium dating techniques to best practices for international cooperation. But it volition be worth the endeavor, because our Paleolithic ancestors, with their faceless humanoids and capacity for silliness, seem to have known something nosotros strain to imagine.

They knew where they stood in the scheme of things, which was not very high, and this seems to have made them laugh. I strongly suspect that nosotros will non survive the mass extinction we have prepared for ourselves unless nosotros too finally get the joke.

This article first appeared in the Baffler magazine

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/dec/12/humans-were-not-centre-stage-ancient-cave-art-painting-lascaux-chauvet-altamira

0 Response to "What Art Form Did They Transition to After Cave Paintings"

Postar um comentário